This is part 2 of a three-part post on Conservatism and Modernity. Part 1 is subtitled “Edmund Burke and Modern Conservatism.”

Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France provides an uncannily prescient diagnosis of where the French revolution — by the impetus of its own logic — would inexorably and self-destructively lead. But more important is that this diagnosis rests upon an awareness of a fundamental transformation taking place in the manner by which the past, present, and future are to be linked to one another. The real revolution is not taking place in “the affairs of France alone” with the dethroning of a king. The real revolution is an emerging worldview that is predicated on dethroning all the institutional structures, customs, and traditions of the past in the name of a future yet to be created.

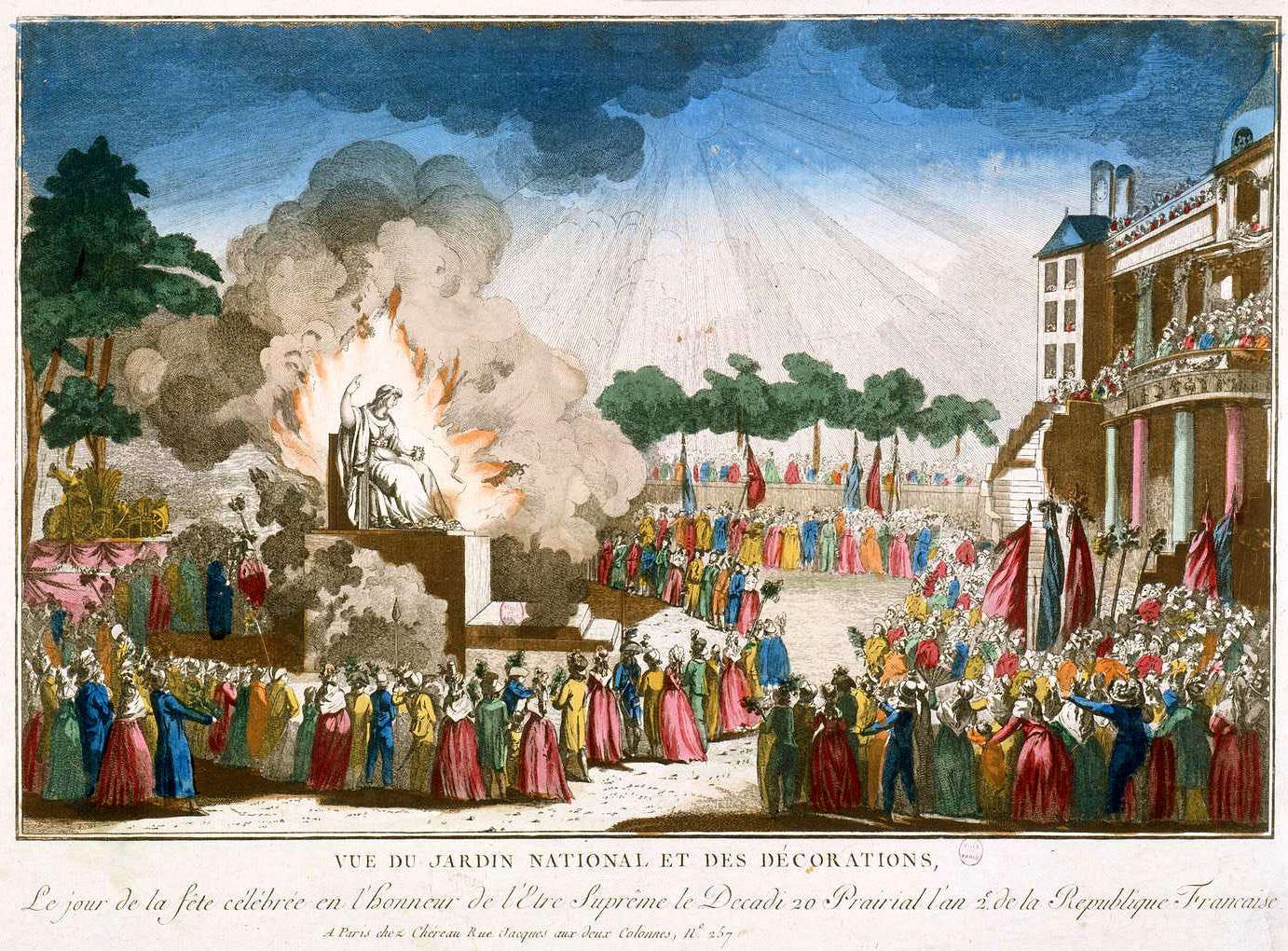

The French social fabric, woven over centuries, did not so much slowly unravel as it was suddenly ravaged by top-down decrees. In quick succession by multiple decrees, Catholicism was replaced by the atheistic and abstract Cult of Reason, and the year 1793 Anno Domini, along with the Gregorian calendar, were supplanted by Year One of the French Revolutionary calendar, thereby inaugurating — so we were told — a new dawn for humanity. Centuries-old social conventions, hierarchies, and titles were likewise replaced overnight by the abstract substrate citoyen, to which were attached the no less abstract rights of liberté, égalité, fraternité — all of which were buttressed not by lived experience or social realities, but by a less-than-fraternal guillotine.

All of this, of course, was in the name of a radiant future that now not only diverges from the past, but also perpetually surpasses the past as humanity is propelled — so it was told — into an era of unprecedented progress. The idea that an unforeseen series of events could so sever the past and traditions from the present, and that the present, now malleable, would in turn be amenable to ceaseless change as it yields to the onslaught of an open-ended future testifies to a new sense of temporality that forcefully emerged by the late-eighteenth century. This was the newly emerging modern worldview that Burke sensed in his Reflections — even as it was unfolding — and without the benefit of hindsight.

The temporal horizon before the late-eighteenth century that Burke fearlessly defended can be envisioned as what Arthur Lovejoy calls a “Great Chain of Being,” in which seamless continuity was the order of the day. True, the capacity for distinguishing between past, present, and future antedates the late-eighteenth century. But before this time, the future was seen less at the expense of the past than in terms of the past. What differentiates a premodern understanding of the future from modern future orientedness is that the former wagers on a future that perpetuates the present, whereas the latter wagers on a future that diverges from the present.

Modern temporality in other words becomes decidedly future-oriented. No longer shackled by the past, no longer timelessly projected unto eschatological expectations, and no longer confined to the repetitiveness of cyclical time, the future instead becomes increasingly seen as both different and superior to the past and the present.

But as we can see now, modern temporality also invites hubris: now that nothing is sacred, save the impetus to attack the sacred, now that nothing lasts, save the motto that nothing lasts, the impetus at work in modern temporality, under the guidance of a newly created political intelligentsia, can now impetuously fancy that humanity can be consciously molded by its own hands. It can now heedlessly discard accumulated past wisdom, social institutions, and the very fabric of society, replacing these with abstract blueprints for a new social order unmoored from such pesky irritants and obstacles as concrete lived experience and social reality.

If continuity and tradition, let alone the need to conserve them, were not issues before modernity, this is not because they were inoperative; it is instead because they were all too operative. If indeed the future is not experienced as divergent from the past, then the past can be readily accessed from the present without any epistemological gnashing of teeth and wringing of hands. Before the late-eighteenth century, temporal discontinuity was readily glossed over, the past was perceived as unproblematically accessible, and tradition was so tightly integrated into daily life that it posed few problems aside from the usual inter-generational squabbling.

In such a scenario, there was no need, then, for conservatism. After Burke, conservatism, as an ethos, has been coterminous with modernity. And because a new temporal worldview set modernity in motion, conservatism has been acting, or rather, reacting, to an agenda not of its making yet which it cannot elude.